Home > Essays > The art gallery assistant's quick guide to wine

If you're a gallery assistant at some art gallery, odds are you're going to be assigned to the refreshments table some time in the near future, if you haven't already.

In that position, no one expects you to be a wine connoisseur. But people quite reasonably expect you to know a few basic facts about what you're serving. Like, what is it called? Is it any good? Would you drink it?

Maybe you've heard the bon mot "great people talk about ideas, average people talk about things, small people talk about wine." My god, we must be such small people for talking about wine in detail like this!

But how's this for an idea: if your gallery doesn't properly mind the wine, people will get the wrong idea about your gallery, so then your gallery might go out of business, and then you can just forget about all important ideas the art in your gallery would have hopefully communicated.

When a gallery does wine right, it blends seamlessly into the gallery experience, and helps focus the patrons' attention on the artwork on display, which is what really matters. But when a gallery does wine wrong, it can point up a lack of professionalism and moral integrity.

Those are important qualities for a gallery to appear to have (and to actually have) if people are going to spend hundreds or thousands of dollars on art that is not valued highly by society at large.

And that gets us to the crux of why wine is so important for an art gallery to serve. People think they can see everything in an exhibit in a few minutes, and they think that art is easy to make. Why spend five minutes looking at something that was made in less time than that?

But someone drinks just a little bit of wine, and it encourages them to take a closer look at the artwork. With more time to look, there is more time to make a decision to buy.

But it's not enough to have the same old Merlot and Chardonnay at the table. If you don't know anything about the wine you're serving, maybe you don't know anything about the art on the walls. It's an unfair assumption, but it's one people make all the time.

Fortunately, there is an easy way to get some background information on the wine you're serving. If you only learn one thing from this guide, it should be this:

READ THE LABEL!

Granted that some labels are more informative than others. Some labels just have the bare minimum of information required by retailers and the Government:

That might seem like a lot of information for a label or two ("front" and "back" of the bottle, so to speak), but in some situations, it is insufficient. Some labels also include some or all of the following:

If you don't know how to pronounce the name of a wine, maybe you don't know what it is and maybe you shouldn't be serving it at all. So it is better to say something that is close enough to correct than to not even try.

The names of many wine varieties are French names. With French, you can get a pretty good approximation to correct by pronouncing every letter of a word except the last letter. So, for example, you write "Cabernet" with a T at the end, but you don't pronounce that T.

With Italian names, you have to pronounce every letter. As for names that mix languages, like White Merlot and Pinot Grigio, use your judgement.

There are several different ways to classify wine, with much overlap between classifications.

Grapes look purple or green to me. Presumably the purple grapes make wine that is also purple in color, while the green grapes make wine that is more like yellow in color. But as a matter of convention, these wines are called "red" and "white" respectively.

Red wines are often put in green bottles, though you will also find them in clear bottles. White wines are almost always put in clear bottles; I know of only one white wine in a blue bottle, and that's Winter White from Leelanau Cellars.

Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot are the typical red wines served at art galleries. Predictable and boring. Serve Shiraz (or Syrah) and Pinot Noir to mix things up while staying close to the Merlot comfort zone.

Chardonnay is the usual white wine, but I've been seeing Pinot Grigio and Sauvignon Blanc more and more. Mix things up with Riesling and Gewürztraminer. Moscato is a welcome change of pace, in my opinion.

Wine snobs look down on pink wines, or rosé, to try to sound fancy. Rosé wines, at least the better known rosés, tend to be sweet, but fans of Ernest Hemingway might know about Tavel Rosé, which might be confused for a red wine in a blind taste test.

Perhaps it is best to first put out the red and white wines, meanwhile chilling the pink wines (if necessary). When you put out the pink wines, the patrons will perhaps have overcome their snobbery, and realize they do like pink wine after all.

Rosé wines range in color from a light pink to a darker, almost red color. A common misconception is that all rosé wines are made by mixing red and white wine, but blending is just one method.

It seems that more often what vintners will do is start from red grapes but remove the grape skins sooner than they would for a red wine. There is a direct correlation between how much time the skins are left in and the darkness of color of the resulting wine.

Tradition is not always to blame when terminology seems confusing or even wrong somehow. Sometimes you have to blame marketing. That is the case with White Zinfandel. Your regular red Zinfandel (which has been eclipsed in popularity by White Zinfandel) is a red wine. But White Zinfandel is not a white wine, but a pink wine.

Apparently, the folks at Sutter Home were trying to create a Deep Red Zinfandel, and the pink Zinfandel was a byproduct of that. Of course they wouldn't let all that pink Zinfandel just go to waste.

Marketing decided to call the byproduct "White Zinfandel," and it started to take off. I don't know the story behind White Merlot, but that is also a pink wine, and not a white wine like the name leads us to expect.

It seems like an oxymoron to refer to a liquid as being "dry." But that is the terminology for wines that are not sweet, and it is fairly consistently that the term retains its oxymoronic quality across different languages (e.g., a "vin sec" or a "vino secco").

To confuse matters, however, some sweet wines are literally called "half-dry" in other languages, though that term is usually translated to English as "off-dry."

There's not much to explain about a wine being sweet, it's very self-explanatory. What might confuse you is the concept of "dessert" wine: does it take the place of a solid dessert (like cake), or is it meant to accompany a solid dessert?

As it turns out, it's the former; the latter is probably a bad idea because the sweet taste of the solid dessert would probably overpower the taste of the wine.

Dessert wines can be further subclassified into five types, of which most are white wines:

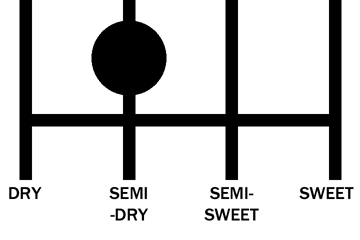

A few vintners are including diagrams like this one on the labels of their wines. This example shows where a semi-dry wine falls on the dryness/sweetness spectrum.

A few vintners are including diagrams like this one on the labels of their wines. This example shows where a semi-dry wine falls on the dryness/sweetness spectrum.Some vintners regard dry and sweet as being extreme ends of a scale, and they seem to think that infinite gradation is possible, at least theoretically. In practice, however, "semi-dry" and "semi-sweet" might be way more gradation than is actually necessary. You might serve the same wine to two different people and they might not agree which one is closer to dry and which one is closer to sweet.

Now to elaborate on sangria. Sometimes the word refers not so much to a wine as to a mixture of grape juice or wine with berries, cherries and chopped larger fruits. At some restaurants, sangria might have such a low alcohol content that you might think they forgot to put any wine in it.

Of course you shouldn't find chopped pineapple and such in a bottled sangria that you buy at the supermarket. What the vintner usually does is add natural and/or artificial flavors to the red wine. Results vary widely in quality.

Of the sangrias that come in bottles, the best one I've ever had was from Oak Creek; CVS used to sell it. Madria Sangria is okay. There are some sangrias which taste like Kool Aid with alcohol, and cause a terrible hangover headache the next day.

If no one on the gallery staff has tried a sangria intended for a reception or other event, it should be pulled until someone can test it at home. The same goes for a sangria mix recipe: if it hasn't been tested privately, it shouldn't be served publicly.

Dryness or sweetness is the most important parameter for matching wine to an occasion. Certainly Jesus didn't have a sweet white wine at His last supper, and communion wine is a dry red wine at room temperature. I was once at a memorial reception at which they served a sweet White Zinfandel. That was inappropriate.

In general, for most art opening receptions, you should serve a dry and a sweet wine. That is more important than having a red and a white, and why I find it annoying and troublesome to see the same old Cabernet Sauvignon (which is always dry) and dry Chardonnay at so many receptions. If at least the Chardonnay was a sweet, late harvest Chardonnay, that would break the monotony.

If the theme of the art exhibit is of the utmost seriousness, then perhaps only dry red wine should be served. For a really fun exhibit, on the other hand, there should also be a semi-dry or semi-sweet white wine and a sweet pink wine.

Without delving too much into the history or the technique of wine making, it should be noted that Sutter Home White Zinfandel was at first not a sweet wine. The vintner had an unintentional "stuck fermentation," they liked the sweet results, and so did the general public. Sutter Home has since then continued to make sweet White Zinfandels, and most if not all of their competitors have gotten in on the act.

But the wine snobs did not like the new sweet White Zinfandel, and they made sure to give all White Zinfandels a bad reputation. There are dry pink wines, including dry White Zinfandels (sometimes marketed as "White Zin"), but you have to look for them, if not in the higher end supermarkets, in shops that specialize in wine.

Classifying wine by function is not as useful as it might seem at first. Take for example cooking wine. Almost any chef will tell you that you shouldn't cook with wine that you would not drink straight. That means that table wines and dessert wines are the real cooking wines, whereas wines that are sold as cooking wines should perhaps be phased out.

If you ask Google "What is table wine?" Google will tell you that it is "wine of moderate quality considered suitable for drinking with a meal." But that doesn't sit so well with vintners who label their table wines as "premier table wine."

The American vintners' definition of table wine seems to have to do more with affordability than with quality. I certainly agree with Leelanau Cellars that their Autumn Harvest is a "premier dry red table wine," and it is affordable at less than $10 a bottle at Kroger.

So in America, a table wine is affordable, not sparkling and not fortified (which seems to knock out only some dessert wines out of the category), and it is dry (which knocks all dessert wines out of the category, and indeed all sweet wines).

But I wouldn't be surprised if there is some American vintner who uses the term "table wine" for a sweet or semi-sweet wine. In Europe, the terminology is a bit more complicated and nuanced.

So for an art gallery, classification of wine by function is almost useless. Basically it boils down to this: if it's sold as "cooking wine," don't buy it. If it is sold as "table wine" or "dessert wine," then it's worth considering.

You should know that if it's not from Champagne in France, then it's not champagne, it's just a sparkling wine. Governments in Europe have gotten very strict about this sort of thing, but casual use in America of words like "champagne" remain common.

I'm not sure if in Europe it is required for a wine to be dry to count as table wine. It seems to mean wine that does not conform to certain more stringent requirements for quality. I'm not going to delve into the various ranks and designations in Europe.

I will just say that the phrases "Vin d'Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée" and "Appellation d'Origine Protégée" designate wines of a specific and verified origin and compliance with the highest European standards for quality.

Now it seems that wine can be made almost anywhere in the world where grapes grow. For American wines, you're not limited to Napa Valley. Michigan has some excellent vintners in the Lower Peninsula, close to the Upper Peninsula, of which I specially recommend Leelanau Cellars.

In addition to American and European wines, you should give serious consideration to Australian wines. Yellow Tail is perhaps the most popular Australian wine sold in America. In general, imported wine is more expensive than California wine, and that makes a perfect segue to our next subtopic.

Depending on the circumstances, you might also be tasked with buying wine, and provided money for that purpose (or reimbursed later). You get what you pay for, and that applies to wine. But you need to be clear on what it is that you're looking to get, and understand that where you buy affects how much you pay.

You're not looking to get something to impress a wine snob; that's probably beyond your gallery's budget. What you are looking to get is something that tastes good, will give your patrons a nice light buzz, and is affordable but doesn't look cheap.

So boxed wine might be fine at home, but is absolutely unacceptable in an art gallery. You want to be able to display the bottles. There was this gallery that used to serve boxed wine.

Someone was nice enough (or stupid enough) to give them a few bottles of wine, not at all expensive, but much classier than anything boxed. The gallery staff served the wine at the next reception and everyone was happy.

For the next reception, however, the staff poured boxed wine into the bottles, which had been presumably rinsed, and presumably the staff took care to match the labels (e.g., not pour boxed Merlot into a Chardonnay bottle). This incident pointed up a severe lack of integrity on the part of the gallery staff. It's not the reason the gallery closed, but it did not help.

Notice the little tab on the foil? You can use it to remove the part of the foil that is in the way of cork removal.

Notice the little tab on the foil? You can use it to remove the part of the foil that is in the way of cork removal.The ideal size is the 750mL bottle (a tiny bit more than 25 ounces). Some stores classify wine bottles by size, putting the 750mL bottles on one side, and the 1.5L bottles on the other side, and then within each side the bottles are further subdivided by brand or variety.

The 1.5L bottles may be a bargain, but they look cheap and not as classy. And furthermore they have the problem that when the reception is over, you might be stuck with a half full bottle, which corresponds to a completely full 750mL bottle.

You can put the cork back in, but the wine might not keep until the next gallery event, whereas with a half full 750mL bottle you can just pour generously to a couple of stragglers. All these problems are exacerbated with the even larger bottles that are also available.

But this is not to say that the 187mL bottles are ideal. Don't get me wrong, they're great for trying out a wine you're on the fence about, like Red Moscato (a dumb idea, in my opinion, but at least I gave it a chance), and it is very petty to fret about "losing" 2mL when you buy a 4-pack of those (but it is appropriate to be concerned about the extra packaging).

Because they tend to be sold in bargain bins for $1, the 187mL bottles have a connotation of cheapness. Really, in an art gallery, the 187mL bottles are a no-win: if you just give someone the bottle, you look lazy, but if you pour it into a cup, you look either stingy or stupid.

For an art gallery, the best place to buy wine is at the higher end supermarkets, though some chain supermarkets have quite a decent selection of wine. You don't want to buy at a convenience store, and that's true for life in general.

I know of one convenience store where they repainted the ceiling and did not bother to move the wines or at least cover them up. I suppose no paint got in the bottles, but do you really want to take that risk? I don't know how often that happens.

What I have almost always found is that convenience stores sell some of the same brands as supermarkets, but at higher prices but with much less care for temperature, exposure to light, time in stock, etc. Don't pay more money for wine that's not properly cared for.

Also, if a white wine looks orange rather than yellow in color, it could be so old it has gone bad. Don't buy it. If you wouldn't drink it, you shouldn't serve it.

If you can afford the gas to get there, the very best way to get wine is directly from the vintner. If you let them know it's for an art gallery, they might give you a very nice discount. Not for free, but much better than what you can get at a big box supermarket.

Serving wine in an art gallery is not the same as serving wine in a bar or at a party. There are many details in common, but there are also details that are different enough to signal an awareness, or a lack of awareness, of the occasion.

Some wines need to be chilled (all sparkling wines, for example), or even served ice cold (like Leelanau Cellars Summer Sunset). In an ideal world, the label would tell you this explicitly, but even some excellent vintners, like Leelanau Cellars, are inconsistent about providing information on ideal serving temperature.

In the absence of better guidance, follow this rule of thumb: sweet and semi-sweet wines should be chilled, dry and semi-dry wines should never be chilled, except when circumstances threaten to make the wine much hotter than the vintner would recommend (anything higher than 80° F should be cause for concern).

With the foil no longer in the exit path of the cork, the bottle is ready for cork removal.

With the foil no longer in the exit path of the cork, the bottle is ready for cork removal.If you yourself have tried the wine at home, your opinion could count as "better guidance" even if it contradicts the label. In my experience, labels that say the wine can be enjoyed at either room temperature or chilled are always wrong: such wines should really be chilled. And the label for Leelanau Cellars Red gives no guidance at all; I say from experience that one should be chilled, almost but not quite ice cold.

Putting the bottle in the refrigerator (not the freezer) the day before the event might give the best results. If a refrigerator is not available at the site, you might have to buy ice. The ice is for buckets or coolers. The wine bottles are then placed in the buckets or coolers.

But ice cubes should not be put into the wine itself. That is only acceptable when you're at home with an almost empty bottle that is getting too warm. Or in the case of a sangria mix recipe

The freezer should only be used as a last resort when you're crunched for time. It takes longer for wine to freeze than water, but it will certainly freeze if you forget to take it out in time.

Alcohol-free wine will freeze almost as fast as water, but you shouldn't be serving alcohol-free wine in a gallery anyway, and so it shouldn't be an issue at all.

In a fancy restaurant, you would have fancy-looking glasses of different kinds, each appropriate for a specific kind of wine. In an art gallery, however, you should generally use clear plastic cups, which can hold at least 4 ounces but not more than 8 ounces.

If the cup is too big, you might have to pour too much to get it halfway full, and you look like you're trying to get people drunk. But if the cup is too small, a decent pour might overflow the cup, and that also looks bad.

The time to think about this is when you're buying the cups, not at the reception, when you're stuck with whatever you bought.

Be sure to have a cork remover. The two main types of manual device are the "jumping jack" (that's not an official term) and a tool that looks like a Swiss Army knife with fewer tools: usually just a little knife to cut foil, and the screw to go into the cork.

If there is no tab on the foil, use a little knife to make a tear in the foil.

If there is no tab on the foil, use a little knife to make a tear in the foil.There are also automated cork removers, ranging in price from $15 to $300. I don't think they're worth the expense regardless, but I suppose using them would look much more professional than a manual device if you come across a particularly stubborn cork.

Many bottles of wine today are sold with metal caps attached to a somewhat tight ring. On first open, the links between the cap and the ring are broken. You are smart enough not to use a cork remover on a bottle with a metal cap.

But many gallery assistants are not smart enough to remove the foil that corked wines often come with. They drive the corkscrew directly through the foil. Once the cork is out, the foil is gnarly and some of it may have fallen into the wine. That's not good.

Some vintners provide a little tab on the foil. Just pull on the tab, and the foil over the cork is neatly removed. If there is no tab, use a little knife set aside for the purpose (not a knife that you use for artwork) to make a tear in the foil, and then use one hand to remove it completely (making sure to hold the bottle with the other hand).

Once the foil is complete removed, or at least out of the cork's path, you can use the cork remover. Try to center the screw tip on the cork, and drive the screw straight down. It doesn't have to be perfect, but if it goes in too far from the center, or at too much of an angle, you might have problems.

A "jumping jack" cork remover in action

A "jumping jack" cork remover in actionWith the "jumping jack" corkscrew, make sure to keep your fingers away from the gear teeth as you push down on the arms. In general, don't go faster than necessary. Better to make someone wait a minute than to damage the bottle, or, more seriously, hurt yourself.

If using an automatic cork remover, be sure to read all the instructions and follow them to the letter. You might also have to worry about people stealing the device.

Some sparkling wines, especially those that are erroneously called "champagne," come with a twisted wire that prevents the cork (whether it be a real cork or a plastic cork) from popping out prematurely.

Be sure to read and follow the instructions on a bottle with such a wire each and every time. People have hurt themselves with sparkling wine corks that popped out forcefully and then bounced around unpredictably.

And remember: the warmer a sparkling wine is, the more forcefully the cork will come out. That is why a sparkling wine should be put in the chilling bucket first, and then opened later. Not the other way around.

The bottles should be on the refreshment table for the people to look at. Generally, only one bottle of each type of wine should be open at a time. It makes no sense to open, for example, two 750mL bottles of Cardiff Merlot one right after the other. Once a bottle is empty or almost empty, that's the time to open the next one of the same vintner and variety.

Your pour should be neither generous nor stingy. Hopefully you thought about this when you were buying the cups. Now that you're about to pour is way too late to be thinking about what the ideal cup size is.

How many cups should you pour in advance? That's a judgement call that will depend, first and foremost, on how many people are in the gallery, and at what pace they are coming and going. You don't want too many out in advance, nor too few.

Generally, only one bottle each of red, white and pink wine should be open at a time, with the poured cups corresponding to the currently open bottles. You can have, say, two reds open at one time, but it might get a little harder to keep track of which cup contains what wine.

In the case of chilled wines, it might be best to err on the side of too few, so that the wine in the cups doesn't get too warm too quickly. When the wine is still in the bottle, even an open bottle, it is relatively easy to put it back in ice if necessary. But once it's in a cup, forget about trying to get it chilled again.

Any time you serve alcohol you run the risk of having people drink more than they should. If you follow the advice in this guide, the risk will be minimal but still there.

If you honestly think the person demanding another cup of wine won't remember the next morning anything that happened tonight, you might want to cut them off. But if there is any malice whatsoever in your decision to cut someone off, they might actually remember the next morning.

I remember one time at this gallery downtown, this guy, we'll call him "Sam" to protect his privacy, he had drunk more than he should have. There was a computer that was controlling one artwork, or maybe it was just looping a video. Sam got on that computer, and naturally the gallery staff were frightened.

Apparently, Sam called for me, assuming perhaps that I might be some sort of computer genius. "How do I check my e-mail on this thing?" Sam asked me. I was puzzled at first, but fortunately the right words came to me: "It can wait until Monday," I said. It was on a Friday, or maybe a Saturday. "You're right, it can wait until Monday," Sam said, or at least I think that's what he said.

If you honestly think having one more drink may cause someone to interact inappropriately with the artwork, then it's time to cut them off. Better to deal with the temporary annoyance of a patron than with the more permanent annoyance of an artist whose artwork was damaged.

Crackers, cheese cubes, fruits, that's what's typically served at art gallery opening receptions. There might be some exceptions I don't know about, but as far as I know all wines go well with cheese and fruits. The issue of meal pairings is thus usually irrelevant in an art gallery.

However, there are sometimes more substantial meals served at art galleries, whether it's because the owner pays for it or because the director allows an aspiring chef to have a pop-up at the gallery.

Then the issue of meal pairings becomes one of high importance. Hopefully the chef knows something about this. But in the absence of other guidance, use this rule of thumb: beef goes well with red wines, fish goes well with white wines.

The label is the first place you should look for guidance on meal pairing. For example, the "back" label of Leelanau Cellars Autumn Harvest starts off thus: "Autumn Harvest is a dry red wine that goes particularly well with beef, venison, lamb, duck and pasta."

Maybe Autumn Harvest also goes well with chicken, but fish would probably be a bad idea. The listing is by no means exhaustive, but it provides an excellent starting point for figuring out how it goes with meals not listed.

If the label for this particular wine said nothing about meal pairing, we would have to fall back on the rule of thumb, and it might not occur to us to try pairing the wine with duck.

Many people believe that sulfites in wine cause headaches. The science seems to say this is not the case. Other people blame tannins. And of course teetotalers blame just plain drinking.

From my personal experience, the quantity and quality of food consumed before wine is a much better predictor of the severity of a hangover the next morning, or not having a hangover at all.

Eat a good, full meal with a nice glass of wine, and you most likely will wake up feeling quite refreshed the next morning. Drink on an empty stomach, be ready for a horrible headache the next morning.

If you serve alcohol, you must also serve water. It's as simple as that.

And also, some people get dehydrated very easily. It's just not worthwhile to risk death to look at artwork you might not even like anyway.

I know, that's melodramatic. But people don't need melodramatic reasons to leave an art gallery soon after arriving. Someone is a little thirsty for water, you don't have any, and the art seems to be the same run-of-the-mill avant-garde other galleries are showing. So someone leaves without taking a closer look at the artwork.

One time at a gallery, someone actually said to me: "We have Chardonnay, that's like water." If a comedian had said that in a stand-up act, I might have laughed. But this was real life. It's not something you want to hear from someone who wants you to come to their gallery and buy art.

This needs to be very clear: wine is not water. It takes a miracle by Jesus to turn water into wine. To turn wine into water, that would also be a miracle, though perhaps not a miracle people would appreciate.

Water can also help keep people from getting too drunk. I can believe that if there is no water, some people who do want water at a particular moment might decide to just have some more wine.

A "jumping jack" cork remover usually also has a beer bottle opener.

A "jumping jack" cork remover usually also has a beer bottle opener.For some exhibits, it may be appropriate to serve beer in addition to or instead of wine. That's a decision to be made by the curator of the exhibit in consultation with the art director and the owner of the gallery.

The problem with drinking both beer and wine in the same evening is that it is too easy to lose track of how much you're drinking. Add liquor to the mix, and the problem is compounded to the point you get drunks trying to check their e-mail on the computer in the gallery space.

On the bright side, beer presents perhaps even more opportunities than wine to showcase local product. In Detroit, for example, there are at least three local breweries which are quite well known. Apparently there are vintners, too, but they have yet to make a reputation for themselves on par with the breweries.

The keg is an attractive option to serve beer to several people at a public event. But make sure to pump the keg for people and to serve them, so as to not let them make unsanitary mistakes in serving themselves, like directly touching the spout.

For beer bottles, note that the "jumping jack" cork remover usually also includes a beer bottle opener. If you have bottles of beer, don't remove the caps in advance, nor let people do it themselves, you have to do it for them.

People will donate money at the refreshment table. But there has to be some kind of tip jar to enable them to do so; if it's not there, people will assume donations are not wanted at the table. That's a lesson I learned the hard way.

The tip jar is ideally a clear glass container, "initialized" with a $5 or a $10 bill. It may be appropriate to have a sign that says something like "Suggested Donation: $2."

Anything more than that is silly. One time at a pop-up, I saw a sign with a whole paragraph asserting that the artists worked very hard on the art and whining about how expensive booze is. I doubt that left anyone with a positive impression of the artists.

How hard the artists worked ought to be obvious from the art on the walls. And if you're worried about the price of booze so much that you feel the need to present a statement about it, maybe you should be a bartender rather than an artist.

If you require someone to give the suggested donation amount before serving them a glass of wine, then it's no longer a suggested donation, it is a required price. There is a time and a place for a cash bar, but in art gallery, it sends bad unintentional messages.

Such as "You cheapskates won't buy any art, so you might as well pay up for the booze." Or "We won't take you seriously if you don't have money." Or perhaps worst of all, "We are not honest enough to label this a cash bar, which is what it is."

It is much more important that people buy artwork than that they give a few dollars for a drink. Encouraging art work sales, that's the whole point of all this. If you're relying on the tip jar to bring in enough money to keep the gallery open, then your gallery is in trouble. Though maybe that's better than relying on charging artists entry fees to consider their artwork for exhibition.

I have curated group shows, I know what it's like to see someone to talk to one of your artists for a half hour and then not buy any artwork. The decision to buy art is not just a commitment of money, but also of time and space.

If I had insisted at those group shows that everyone must pay for their drinks, I would have wound up discouraging people from talking to the artists, and thus eliminated even the possibility of a sale. You want to remove roadblocks to artwork sales, not create them.

And sure, some people will take advantage to get wasted on free drinks. Why begrudge them that? They will suffer the hangover, not you. Plus they might be starving artists, or they might be people who later become rich, and they will remember who was petty to them when they were poor.

You make change from a cash register, not from a tip jar. Ideally, only the gallery treasurer removes money from the gallery tip jar. But if a visitor wants to make change from the tip jar, don't argue with them, let them. Violating the no change rule is a minor price to pay for keeping things cordial.

Water should not be an afterthought, it must be provided first and foremost whenever alcohol is served. The ideal size of bottle of wines to buy is 750mL. If the food at the reception is anything more than cheese, crackers and fruit, meal pairing of wine needs to be thought out.

The purpose of serving wine is to encourage sales of artwork, not to make a few dollars in tips. You should know a little something about the wine you're serving so that people can have confidence that you're also knowledgeable about the artwork.

And the most important lesson from all this: READ THE LABEL!